On the meaning of forest.

Part I of II.

According to official government figures, forests comprised 66 million acres of the West Coast of the United States (excluding

Alaska) at the time of the first mandated survey in 1933 and 63 million acres

years later, in 1992, after the timber extraction industry had become a timber

farming industry. That’s only a 4.5%

loss after decades of peak extraction.

So what’s the problem?

Defenders of the timber industry cite the fact that more

wood is grown in a year than is removed from forests, a statistic that is supposed

to shut environmentalists up. But those

lamenting the loss of the West Coast’s forests aren’t wrong. The methodology is.

Statistics are arrived at through the use of methodological

choice, a choice made by humans. Any

methodology looking for answers on deforestation starts with a value-laden

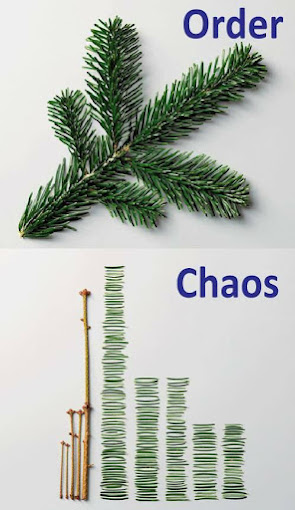

philosophical question: “How should we define the word forest?” It seems like an

easy question with an obvious answer, but it isn’t and the answer is far from

obvious.